Condonomics Debunked: A review of Patrick Condon's 'Broken City'

In Broken City, landscape architect Patrick Condon presents a diagnosis of the housing crisis. Condon claims to be a pragmatic empiricist, but he actually relies on extreme theoretical scenarios. He thinks in memes, not models. The result is a flawed analysis of housing policy. Condon misunderstands the relationship between land and housing prices, and incorrectly identifies upzoning as the main cause of the housing crisis. This leads him to reject supply and demand theory entirely. Applying this erroneous framework to inclusionary zoning and development taxes, Condon recommends policies that would worsen housing affordability.

I. An incoherent theory of land values

Condon’s thesis is that rising land values are responsible for increasing housing costs:

The thesis of this volume […] is that the housing crisis is not caused by an impeded supply of homes but by the asset value of the land below them. This Rent value is inflated when higher-density homes are authorized, much to the disappointment of those who argue that the housing-affordability problem is caused by constrained supply. (p.177)

In other words, since land is an input into the production of housing, higher land values will drive up housing costs. And upzoning in particular is a primary cause of higher land values. This view is superficially plausible. As a naive empiricist, Condon has observed rising housing prices and land values coincide with upzonings. But what is the actual causal relationship underlying these correlations?

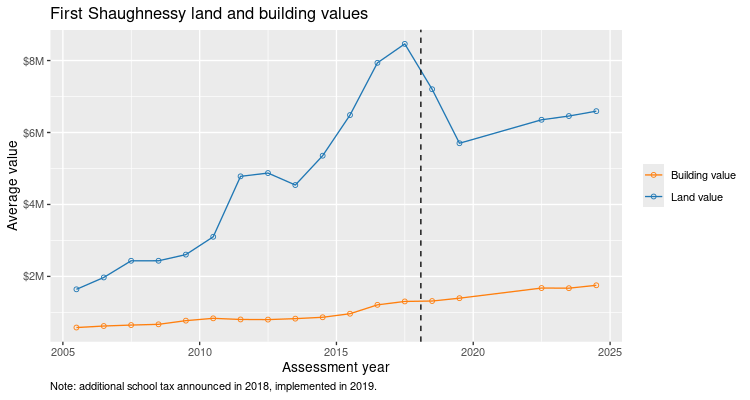

Condon thinks that upzoning drives land values, which in turn causes higher housing prices. Right away we can find a fatal flaw in this view: in First Shaughnessy, a heritage-protected mansion neighborhood in Vancouver, land values quintupled between 2006 and 2017 (before decreasing after a property tax was implemented). Over the same period, building values doubled.

Code

library(VancouvR)

library(tidyverse)

# time series plot of average land and building values in First Shaughnessy

# remove upzoned parcels and character infill

# if zoning changes, then no longer FSD

# hence, require that zoning is FSD in all years

# use assessment date: July 1 of previous year

fsd_data <- search_cov_datasets("tax")$dataset_id |>

map_df(\(ds)get_cov_data(ds, where = "zoning_district= 'FSD'",

select = "pid,land_coordinate,zoning_district,neighbourhood_code,report_year,current_land_value,current_improvement_value")) |>

mutate(n=n(),.by=land_coordinate) # count number of times a parcel appears

est_data <- tibble(Date=as.Date(c("2018-02-01")), label=c("Announced"))

png(file=paste0("shaughnessy.png"), width=750, height=400, res=90)

fsd_data |>

# keep parcels with 18 observations as FSD

# if >18, then multiple conversion dwelling: multiple dwellings per parcel

filter(n==length(unique(fsd_data$report_year))) |>

summarize(`Land value`=mean(current_land_value),

`Building value`= mean(current_improvement_value),

.by=report_year) |>

mutate(Date=as.Date(paste0(as.integer(report_year)-1,"-07-01"))) |>

arrange(Date) |>

pivot_longer(cols=c(`Land value`, `Building value`), names_to="type", values_to="value") |>

ggplot(aes(x=Date, y=value, colour=type)) +

geom_line() +

geom_point(shape=21) +

geom_vline(data=est_data, aes(xintercept=Date), colour="black", linetype="dashed") +

scale_y_continuous(labels=\(x) scales::dollar(x, scale=10^-6, suffix="M")) +

scale_color_manual(values=c("Land value"="#1F77B4", "Building value"="#FF7F0E")) +

labs(

title="First Shaughnessy land and building values",

x="Assessment year",

y="Average value",

colour=NULL,

caption="Note: extra school tax announced in 2018, implemented in 2019."

) +

guides(linetype="none") + # removes legend entry for vline

theme(plot.caption = element_text(hjust = 0) # left-align caption

, legend.position = "right",

legend.justification = "center"

)

dev.off()

# same graph for rest of Vancouver

nonfsd_data <- search_cov_datasets("tax")$dataset_id |>

map_df(\(ds)get_cov_data(ds, where = "zoning_district != 'FSD'",

select = "pid,land_coordinate,zoning_district,neighbourhood_code,report_year,current_land_value,current_improvement_value")) |>

mutate(n=n(),.by=land_coordinate) # count number of times a parcel appears

png(file=paste0("non_shaughnessy.png"), width=750, height=400, res=90)

nonfsd_data |>

filter(is.na(current_land_value)==0 & is.na(current_improvement_value)==0) |>

summarize(`Land value`=mean(current_land_value),

`Building value`= mean(current_improvement_value),

.by=report_year) |>

mutate(Date=as.Date(paste0(as.integer(report_year)-1,"-07-01"))) |>

arrange(Date) |>

pivot_longer(cols=c(`Land value`, `Building value`), names_to="type", values_to="value") |>

ggplot(aes(x=Date, y=value, colour=type)) +

geom_line() +

geom_point(shape=21) +

geom_vline(data=est_data, aes(xintercept=Date), colour="black", linetype="dashed") +

scale_y_continuous(labels=\(x) scales::dollar(x, scale=10^-6, suffix="M")) +

scale_color_manual(values=c("Land value"="#1F77B4", "Building value"="#FF7F0E")) +

labs(

title="Vancouver land and building values (excluding First Shaughnessy)",

x="Assessment year",

y="Average value",

colour=NULL,

caption="Note: additional school tax announced in 2018, implemented in 2019."

) +

guides(linetype="none") + # removes legend entry for vline

theme(plot.caption = element_text(hjust = 0) # left-align caption

, legend.position = "right",

legend.justification = "center"

)

dev.off()

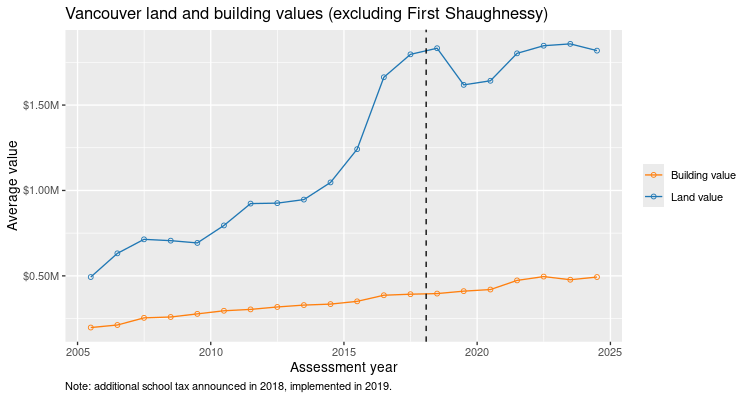

The entire neighborhood of First Shaughnessy is a heritage conservation area, so we have a clean natural experiment: very few upzonings are happening here (and any rezoned parcels are removed from the data), and yet land values are soaring. Moreover, the pattern in the rest of Vancouver is almost identical; so land values are increasing whether or not upzonings occur.1

But then what is causing the increase in land values? Condon has no answer. He could appeal to speculators bidding up parcels in anticipation of future upzonings, but when the entire neighborhood is heritage-protected, this is obviously strained. Hence, we can discard his thesis.

So what is the correct model of housing and land values?

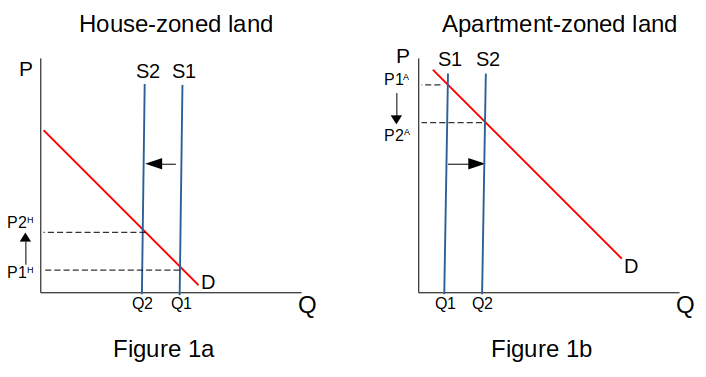

Consider a simplified setting where land is zoned for either detached houses or six-storey apartments; developers can build houses on house-zoned or apartment-zoned land, and can build apartments only on apartment-zoned land. Upzoning means reallocating a parcel from house-zoning to apartment-zoning. This makes apartment-zoned land more abundant and hence cheaper (Figure 1b), while house-zoned land becomes scarcer and more expensive (Figure 1a). Since land is an input into housing, upzoning makes apartments cheaper and houses more expensive.2 (See here for a full writeup.)

A supply and demand model of upzoning and land prices

A supply and demand model of upzoning and land prices

Condon does get one thing right: the upzoned parcel itself increases in value as it switches markets (from \(P_1^H\) to \(P_2^A\)). But this ‘own-parcel effect’ is irrelevant for evaluating upzoning. Developers make decisions based on the market-wide price, not the price of a single parcel. Upzoning reduces costs for apartment-developers, because it reduces the price of apartment-zoned land. The upzoned parcel itself was previously legally unavailable to apartment-developers, so making it available at some price is an unambiguous improvement.

In this model, housing demand is the main driver of land values. When demand to live in the city increases while supply is constrained, housing prices go up, which raises developers’ willingness-to-pay for land. This is why land values in First Shaughnessy quintupled: Vancouver became more attractive to global-elite CEO types who want to live in a mansion. Hence, the cause of the housing crisis is housing demand growing faster than supply, with rising land values being a symptom. So Condon has misdiagnosed the problem, confusing cause with effect.

We can also see the problem with Condon’s thesis by applying it more generally. His view implies that it’s never worth it to upgrade something, because upgrading just increases the cost. For example, processing iron ore into steel just means you have to pay more for the finished product. Let’s apply Condon’s thesis from above to steel:

the [steel] crisis is not caused by an impeded supply of [steel] but by the asset value of [iron ore]. This Rent value is inflated when [ore-processing is] authorized, much to the disappointment of those who argue that the [steel]-affordability problem is caused by constrained supply.

But of course, manufacturers can’t use iron ore, just as apartment-developers can’t use house-zoned land. And the increased availability of steel makes it cheaper, so manufacturers are actually better off, just as apartment-developers are better off when apartment-zoned land is cheaper.

II. A dogmatic rejection of supply and demand

In Condon’s worldview, supply and demand cannot explain the housing market:

The theory of supply and demand has been undercut by the observed economic reality […] that no matter how many new housing units a metropolitan area adds, housing prices continue to rise. (p.56)

Condon attributes the problem to land values:

[The] increase in urban land price seems to be caused by factors other than the supply and demand for new homes. The increase has to do with the innate limits on the availability of urban land and with how these limits make land perform uniquely in the global marketplace for “real” assets. (p.56)

For Condon, housing demand doesn’t affect land prices, so he needs to find some other factor to explain why land values have increased. As we’ve seen, his attempt to pin the problem on upzoning fails, and with it, his attempt to disprove supply and demand.

In fact, a supply and demand model can neatly explain the data. Demand to live in cities like Vancouver has increased, and restrictive zoning has prevented supply from keeping up. This supply and demand mismatch causes both higher housing prices and higher land values.

Condon is fond of claiming that Vancouver’s city center has tripled the stock of homes, yet prices remain very high. He is simply unable to conceive of demand being a cause of housing prices.

III. A reliance on theoretical edge cases

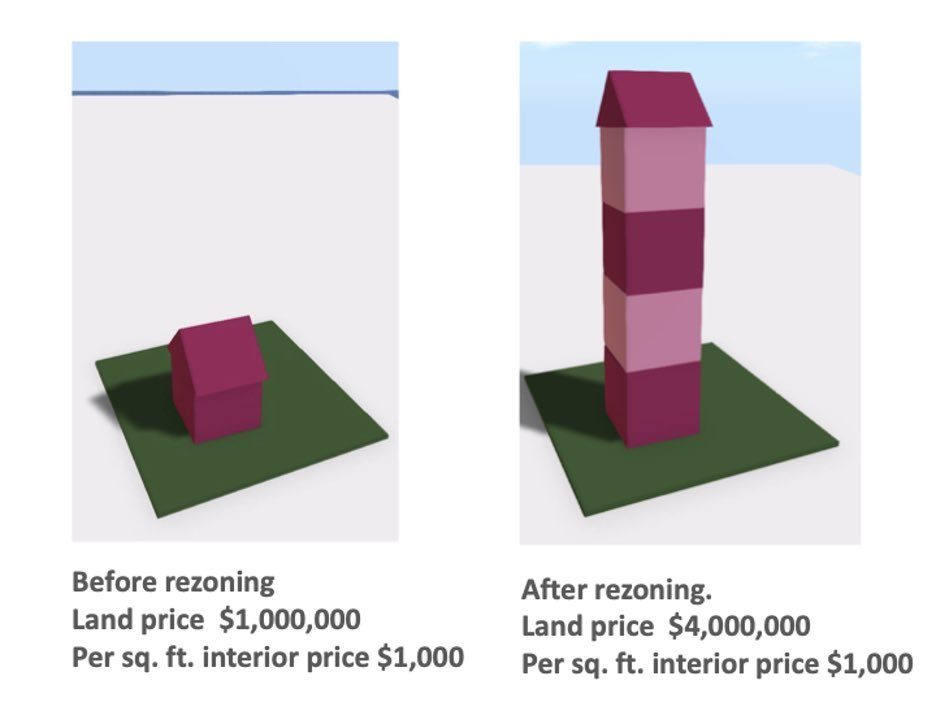

To see how Condon uses extreme theoretical edge cases, let’s consider his numerical example showing that upzoning merely increases land values:

Imagine a parcel of 4,000 square feet with an allowable floor surface ratio of one (FSR 1) that sells for $2 million dollars prior to rezoning. If the allowable density is doubled to a floor surface ratio of two (FSR 2), the redevelopment value increases in kind, forcing a near doubling in the value of the land to $4 million. Why?

When the city authorities a doubling of market density without requiring affordability, the residual land price goes up in response. The city gets more efficient use of the land with the new density – all good – but gets no substantial decrease in the [price] per square foot of new housing. […]

In this example, with a market sale price of $1,000 per square foot of usable interior space, the developer would calculate a land-price residual of $500 per buildable square foot because that is what is left after paying for construction (at $250 per square foot) and for fees, constants, and profits (at a total of $250 per square foot). The developer can afford only up to $500 per buildable square foot, or roughly $4 million for land (i.e., 8,000 interior square feet at $500 per buildable square foot). […] But note the land-price residual has doubled from $2 million to $4 million. And if the developer refuses to pay the $4 million, some other developer certainly will. (p.195-96)3

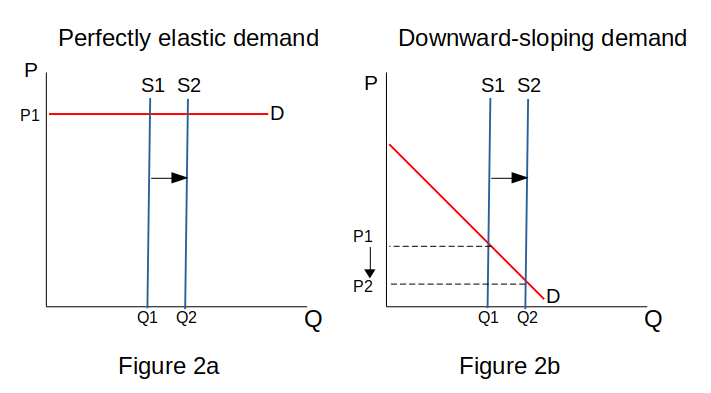

Note the last sentence: this entire argument depends on this tacked-on clause, though Condon does not realize it. When would a developer be willing to pay $4 million? Only when demand for housing is perfectly elastic, so the demand curve is horizontal (see Fig 2a below). In this case, shifting the supply of housing doesn’t reduce the price, because supply always intersects demand at the same price. So Condon is simply assuming that upzoning does not reduce housing prices.

If we relax this assumption, then the demand curve slopes downward (as usual), and increasing supply reduces the price (Fig 2b).4 For example, if a mass upzoning increases supply and causes housing prices to fall to $900psf, then the land price residual is now $400psf instead of $500psf. Hence, developers would only be willing to pay $400*8000 = $3.2M, instead of $4M.5 Notice what happened: land values went up and housing prices went down; but according to Condon, this should be impossible.

The effect of increased housing supply for different demand curves

The effect of increased housing supply for different demand curves

Another problem is that Condon is focused on the land price of a single parcel, instead of the market-wide price of each type of land. When the parcel is upzoned, it switches from 1-FSR to 2-FSR. This makes the set of all 1-FSR parcels smaller by one, and the set of all 2-FSR parcels bigger by one. So 1-FSR land becomes more expensive and 2-FSR land becomes cheaper. But Condon completely ignores this effect, because he does not track land prices by type before and after the upzoning.

Finally, this argument doesn’t even support Condon’s thesis. His claim is that higher land values are the cause of higher housing prices, and that upzoning is the main cause of rising land values. But in this example, the goalposts have shifted: now the goal is to show that upzoning does not reduce housing prices. That’s because Condon doesn’t have a model of prices; by assuming perfectly elastic demand, he effectively takes prices as fixed, and determined outside of the model. Hence, even if we set aside the reliance on a theoretical edge case, Condon is unable to support his thesis that upzoning increases housing prices.

IV. A backwards analysis of inclusionary zoning

Condon favors inclusionary zoning (IZ) as a solution to the housing crisis, because it reduces land values. Under the ‘density bonus’ version of IZ discussed by Condon (from Cambridge, MA), developers are granted permission to build extra density in exchange for making all units in the project Affordable (that is, available at subsidized prices).

Continuing the numerical example from above, if the city imposes a housing price of $750psf on the new Affordable units, then the developer’s willingness-to-pay for land is: $750psf - $500psf = $250psf. For 8,000sf (at FSR=2), this means the developer will pay up to $2M for the parcel, compared to $4M in the market-rate upzoning scenario.

For Condon, IZ reduces housing prices because it reduces land values:

In this example, if a nonprofit housing corporation or co-op is assumed, the selling price per square foot drops from $1,000 to $750, with all of this price reduction attributable to lower land cost (p.197).

But this gets the causality backwards. The lower housing price is not ‘attributable’ to the lower land price; rather, the regulated housing price directly causes the lower land price. By artificially controlling the housing price, we reduce developers’ willingness-to-pay for land, which in turn reduces the land price. So the land price is a symptom, not a cause.6

Condon mistakenly implies that IZ works like a cost-reduction policy, by reducing the price of housing inputs (namely, land). But IZ is a non-market policy. It has no direct effect on the market forces that led to a housing price of $1,000psf.7 Using IZ to reduce land costs is like dipping a thermometer in cold water to reduce the air temperature.

This is an important point. IZ doesn’t address the question of how we make market-rate housing more affordable. Even though the vast majority of people live in market housing, Condon has no answers for them. Because he rejects supply and demand, Condon has given up on fixing the housing market, and instead wants to switch to a non-market approach.

While IZ is better than doing nothing, it is still worse than simple upzoning. With Condon’s version of IZ, the supply of market-rate housing cannot respond to increases in high-end demand, because only new subsidized units are allowed. This causes a demand cascade, where unabsorbed demand at the top of the market cascades down and increases competition for low-end homes, which in turn forces poorer residents to look for non-market housing. Hence, while IZ does increase the supply of subsidized homes, it also increases the need for subsidized housing. IZ is self-defeating.8

Original meme for context

Original meme for context

V. A failure of value capture

And we can do land value capture in a market system. Using my upzoning example above, when we relax the assumption of perfectly elastic demand, housing prices fall from $1000psf to $900psf and the land value increases from $2M to $3.2M. Since the minimum amount the landowner is willing to accept (their reservation price) is $2M, the city could impose a windfall tax of $1.2M on the landowner. In this case, the surplus created by upzoning is split between lower market-rate housing prices and higher land values, which are taxed for public benefit. Again, higher land values are consistent with lower housing prices.9

Because Condon insists that only upzoning can cause higher land values, his approach to value capture is woefully incomplete. As we’ve seen, land values in First Shaughnessy have multiplied, despite zero upzonings. This land lift is driven by increased demand, and cannot be captured by regulations that apply only conditional on redevelopment. Condon’s fixation on upzoning has blinded him to billions of dollars in land lift that should have been captured for public benefit. The solution is to tax land values unconditionally, as with a land value tax.10

Moreover, the same focus on upzoning means that Condon prescribes taxing only new housing, while leaving old housing untouched; this makes him a favorite among NIMBY activists. In fact, we can see in the graph above that the 2019 property tax coincided with a decrease in land values; but Condon appears uninterested in raising taxes that affect all homeowners.

VI. A partial grasp of development taxes

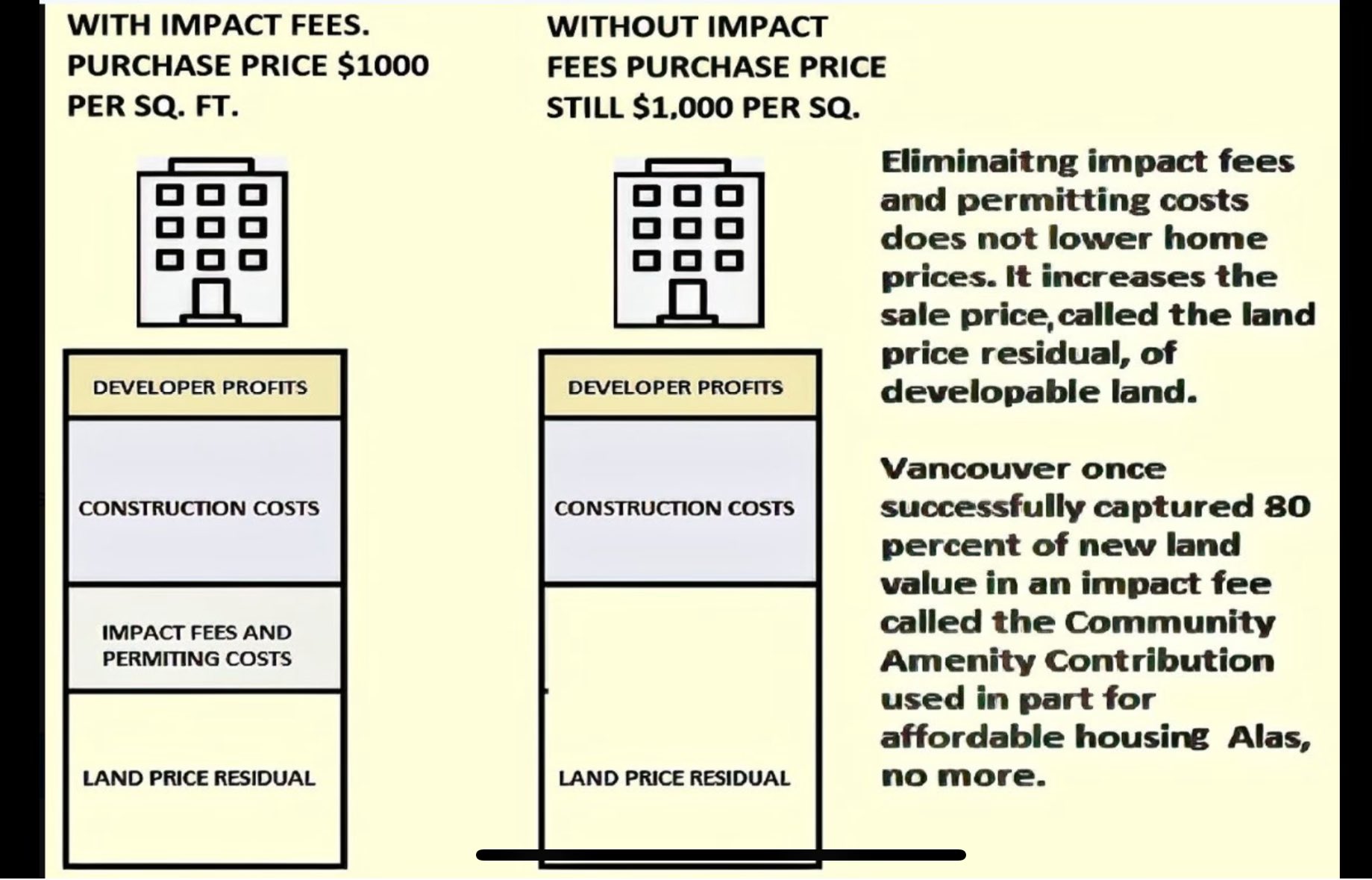

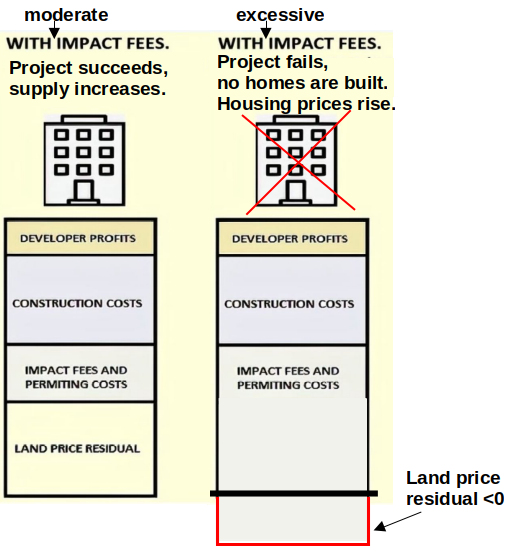

Condon does not have a model of the land market as a whole. Instead he analyzes a single parcel, which leads to a misleading analysis of development charges:

Development taxes […] will affect the residual value of each buildable square foot of a subject parcel. When development taxes are added, the land-price residual goes down, and when development costs are removed, the land-price residual goes up. In this way, development taxes do not add to housing prices for new owners but reduce the residual value per buildable square foot of the development site, thus lowering the money that a developer is able to offer the landowner (p.197-198).11

This is true for a limited context. Specifically, when the tax amount is low enough that the project remains feasible, then the developer does pay less for land. Housing prices are set by the total quantity of homes supplied and demanded; since these haven’t changed, housing prices are unaffected by the tax. So development taxes are another way to implement land value capture.

But more generally, excessive taxes can kill projects, which reduces supply and raises prices. Obviously a tax of $100M would not merely reduce the land price residual. Instead, it would lower the developer’s willingness-to-pay below the landowner’s reservation price, so the transaction would fail and the project would be cancelled. Since the tax reduces the quantity of homes supplied, it raises housing prices. In general, to evaluate the effect of a tax on housing prices, we need to look at the change in the total number of homes.12

Condon doesn’t seem to recognize the risk of killing projects:

However, a development tax imposed late in the approval process may make the business case for a project unworkable. At that point, either the project will be cancelled or the price for the land will be renegotiated down. Municipalities are therefore in a position to moderate or eliminate land-price inflation by signalling their intention, years ahead of time, to impose a development tax. One might call this process disciplining the land market. (p.163)

Again, if projects are cancelled because a tax, then supply is reduced and housing prices are higher compared to the no-tax scenario. The same is true if the tax prevents projects from being started in the first place. Condon does not show an awareness of how taxes affect housing prices, since he is narrowly focused on minimizing land values.

It’s worth spelling out what Condon’s strategy of “disciplining the land market” means. For Condon, housing does not follow supply and demand, so reducing market-rate housing prices is off the table. Instead, our only hope is to make land cheap enough for non-market projects to pencil. This requires imposing enough costs on developers that they stop building new projects, and hence stop offering to buy land at high prices. In turn, landowners would eventually realize that their land won’t sell for a gain, and that they might as well sell it to a non-market developer with a lowball offer. Hence, we get cheap land for non-market housing.13

But as I noted above, this strategy would be a disaster. It does nothing to absorb demand increases, so demand cascades would occur continuously, raising prices and pushing more and more people into needing subsidized housing. Fortunately, Condon’s views are incorrect, and we can improve affordability by upzoning to increase housing supply.

-

We see a similar increase in land values in the rest of Vancouver, where upzoning happens much more frequently compared to First Shaughnessy. So upzoning cannot be main explanatory factor.

↩

↩ -

Equivalently, higher supply of apartment-zoned land increases the supply of apartments, reducing their price. Since apartments are cheaper, the return to owning apartment-zoned land is lower. In a general equilibrium model, land and housing prices are jointly determined; causality runs in both directions. So lower land prices cause lower apartment prices, and lower apartment prices cause lower land prices. ↩

-

Condon has a meme version of this example, where the key point is that housing prices are held fixed by assumption.

By the same logic, upzoning agricultural land to single-family residential doesn’t reduce housing prices, because it just increases land values.

By the same logic, upzoning agricultural land to single-family residential doesn’t reduce housing prices, because it just increases land values.

↩

↩ -

What if inter-city migration makes local housing demand highly elastic? In this case, we evaluate one city’s upzoning in the context of the national market, since lower prices induce in-migration from other cities. Upzoning in city A also reduces prices in B and C, so the effect is scaled down by A’s share of the national population. But the national demand curve is downward-sloping, since immigration into the country is limited, so we get the same analysis as before. In fact, this is just an argument for upzoning nationally, and for zoning policy to be set at higher-level governments to internalize the externalities of local upzoning. ↩

-

Is Condon committing a fallacy of composition here, instead of assuming perfectly elastic demand? That is, upzoning one parcel doesn’t reduce housing prices, but upzoning the entire city would; and Condon is arguing from no effect of upzoning one parcel to no effect of upzoning all parcels. I don’t think this fits. When demand is perfectly elastic, neither a single upzoning nor a mass upzoning has any effect on price. But if demand is downward-sloping, then upzoning even one parcel would decrease the housing price by a tiny amount, say to $999.99psf. But then it’s obvious that a larger upzoning would reduce prices even more. ↩

-

More generally, there’s no necessary connection between lower land values and more-affordable housing. We can always reduce the land price by reducing how much buyers are willing to pay. For example, if we change the zoning to “parking lot only”, the land value will certainly be reduced! But obviously this will not make housing more affordable (in fact, the opposite). ↩

-

Strictly speaking, there is some substitution effect, as new subsidized units reduce demand and prices in the market-rate sector. ↩

-

Versions of IZ that allow some market-rate housing alongside the Affordable units, and hence absorb demand increases, are better than versions that don’t allow any market-rate housing. ↩

-

Condon is focused on reducing land values indirectly, by reducing how much developers are willing to pay for land, so the price doesn’t increase in the first place. As the windfall tax shows, this is not necessary; the city can capture the same land value when the transacted price goes up, by directly taxing the landowner. Also note that a land value tax works like IZ, by reducing developer willingness-to-pay for land. With a LVT, future tax payments are a liability that reduce the value of owning land. ↩

-

An unconditional tax would also solve the problem of landowners shrinking land lift by raising their selling price in anticipation of future upzonings. ↩

-

Condon also has a meme version of this argument.

The key assumption is that fees are less than the land price residual; if fees are larger, then the residual is negative and the project fails.

The key assumption is that fees are less than the land price residual; if fees are larger, then the residual is negative and the project fails.

↩

↩ -

Similarly, a tax cut reduces prices by increasing the quantity of homes, since projects that didn’t pencil with the tax now become feasible. These new homes increase competition between sellers, which drives prices down. ↩

-

“Condon acknowledged that “disciplining the land market” would take time and require certain projects to go unbuilt, at least for a few years. A city council that attempted to do it could be seen as actively blocking new housing construction in a city where more affordable homes are always needed.” Source ↩